According to commonly accepted usage, icons are “written” rather than “painted.” This implies that icons are and speak a language. Like languages, icons are always evolving and changing, and we need to understand the language they are speaking. As iconographer and historian Lynette Martin puts it [1]:

“The pictures are not there just to be looked at as though the worshiper were at an art museum: they are designed to be doors between this world and another world, between people and the Incarnate God, his Mother, or his friends the saints. If a door is to do its job, it must have throughput in two directions. As we move towards an icon, it moves towards us with warm and precise Christian content – if we understand the language that it speaks.“

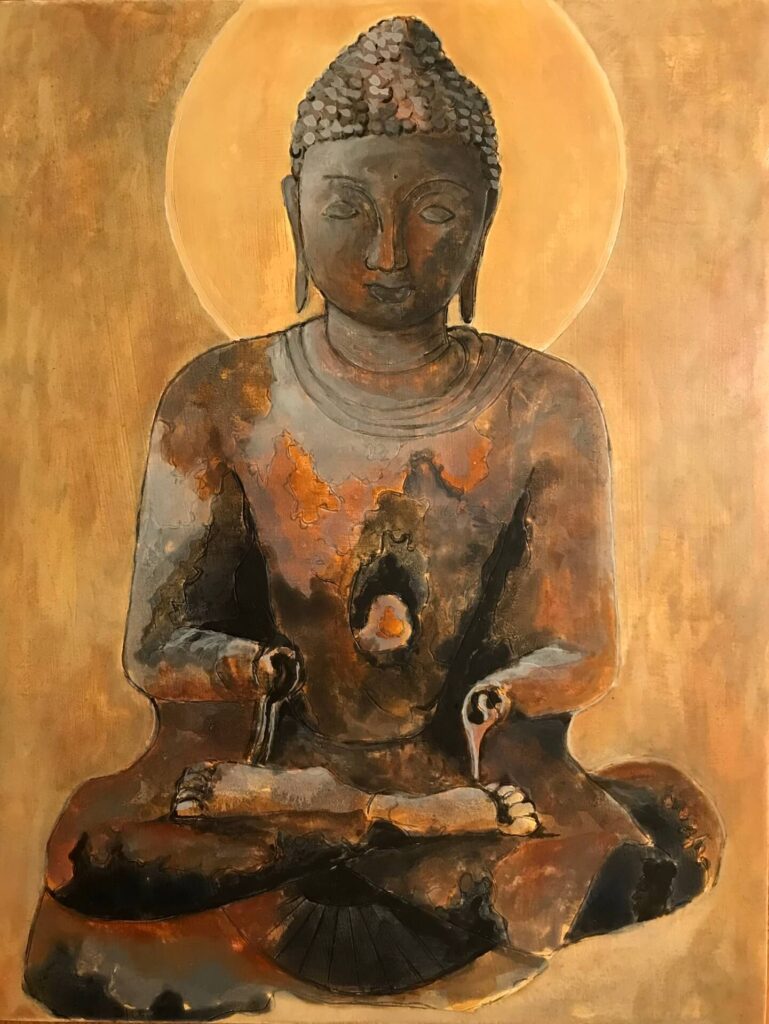

Thinking of icons as doors helped me to see that they can be used to facilitate dialogue and understanding. Since language is always changing, and since I approach the icon from a Buddhist perspective rather than from the theological perspective of the Eastern Orthodox Church, I have given myself the freedom to explore how icons might be written in a different spiritual context. Before doing so, however, I consulted the well-known iconographer Aidan Hart to ask him if it would be appropriate for a Buddhist to use Christian techniques to create Buddhist sacred art.

Aidan Hart wrote back to say that there would be no problem using the same egg tempera techniques in Buddhist painting since the techniques themselves are neutral. With regard to the formal, stylistic elements of Orthodox Christian iconography, some of which are theological, he said it would be up to me to decide if they are appropriate or not to the Buddhist world view. The Christian worldview, he said, is that the material world is good, created by God, and can be seen as a revelation of His love for us. The material world can also be viewed as a physical icon of invisible realities. The icon shows this material world aflame with God’s presence, for God did not just create this world. The divine presence is what sustains it.

I am now planning to use multiple icons to tell a story. As we can see from the iconostasis of Eastern Churches, such use is not original with me. There are also hagiographical icons that include multiple scenes of a saint’s life in one large icon, calendar icons in which saints are written in miniature and arranged in rows, family icons in which each family member’s personal saint is depicted in a single icon, and icons within icons [2].

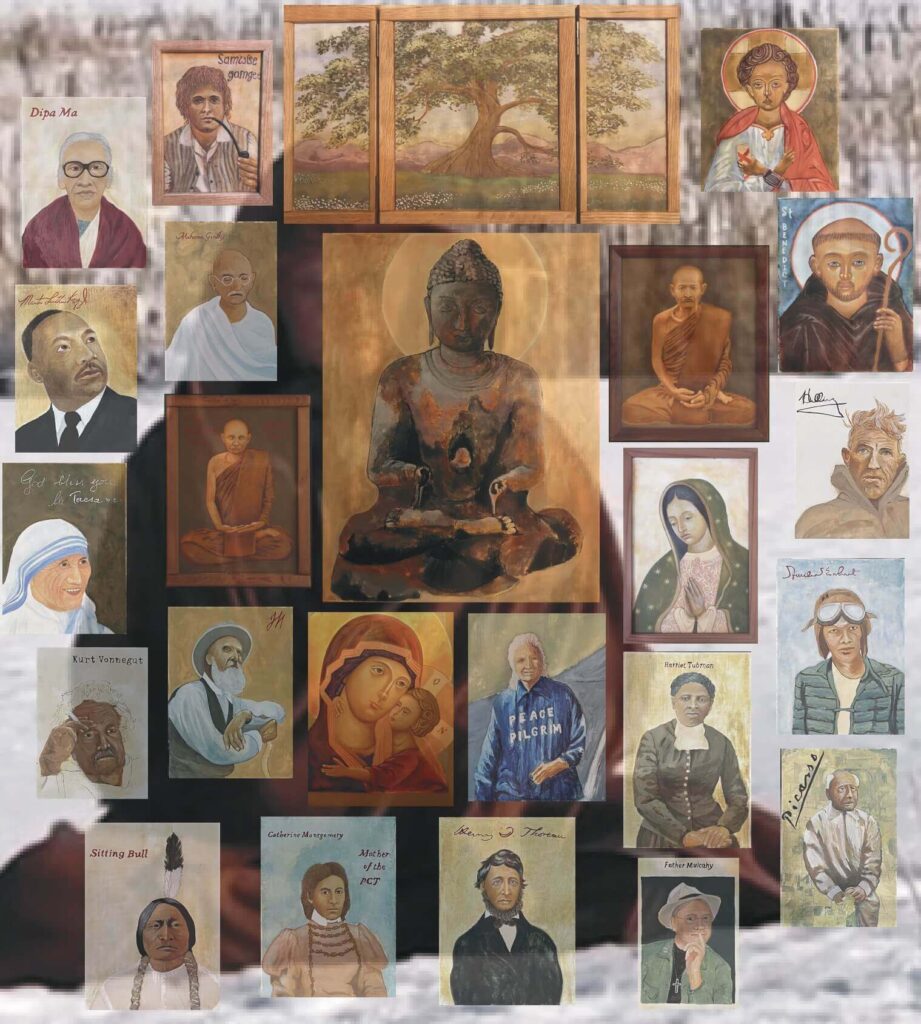

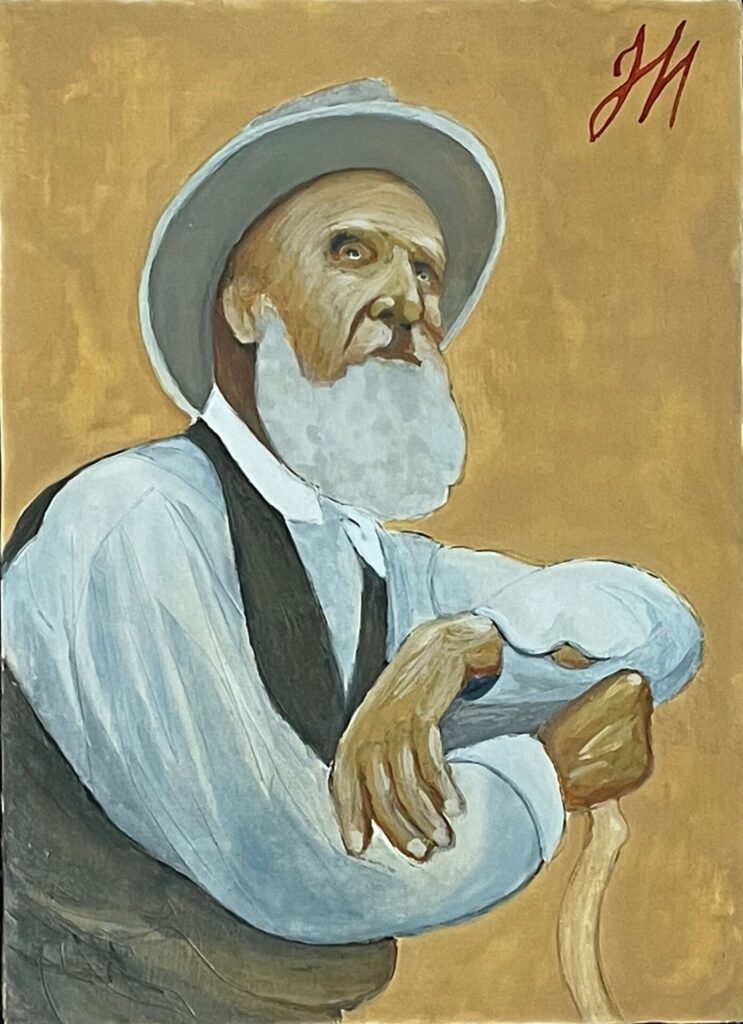

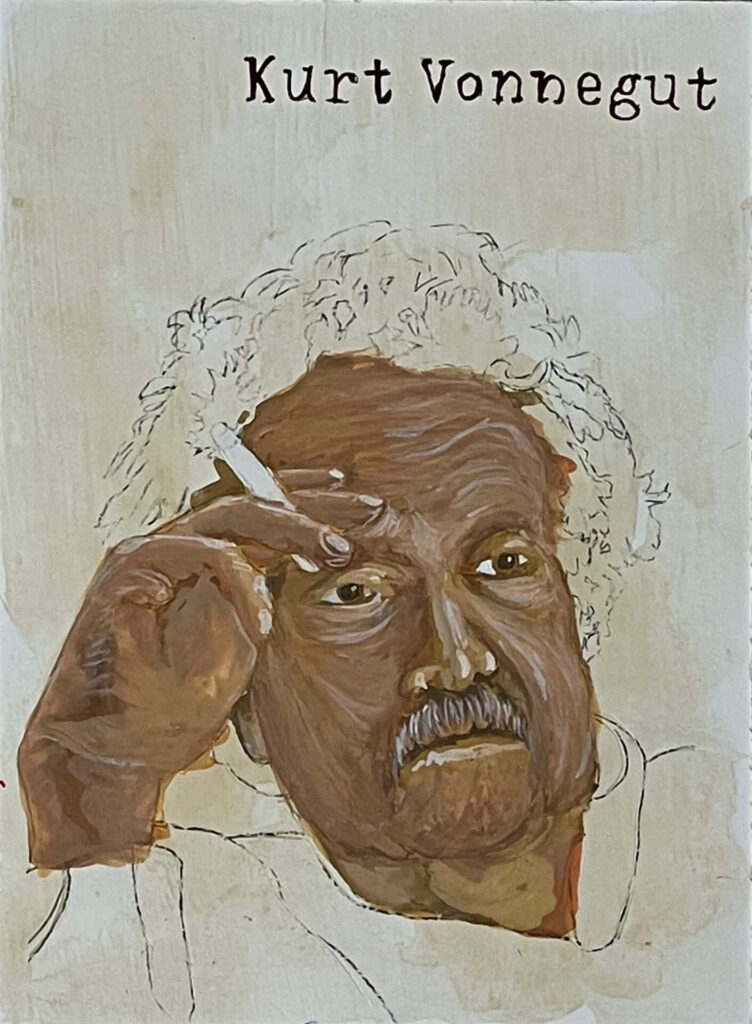

With this way of using icons in mind, I began a series of paintings that I referred to as my Secular Series. My intention was to use egg tempera to produce about 30 portraits of people who in various ways affected my thinking and my values or who represented some aspect of myself that I saw as important.

This project slowly evolved into the idea of creating a collage of about 40 or more paintings that would also include Christian icons, Buddhist images, and even scenes from nature. One of my icon mentors, Fr. Nathanael Hauser, a Benedictine monk at Saint John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota, was intrigued by the idea. I remember him telling me that while icons are usually in dialogue with the worshiper, this collage would create a setting in which icons were in dialogue with each other.

It will be intriguing to see how different arrangements of the paintings create different dialogues.

Notes

- [1] Martin, Lynette. 2002. Sacred Doorways: A Beginner’s Guide to Icons, 15. Paraclete Press.

- [2] Martin, Lynette. 2002. Sacred Doorways: A Beginner’s Guide to Icons, 72. Paraclete Press.